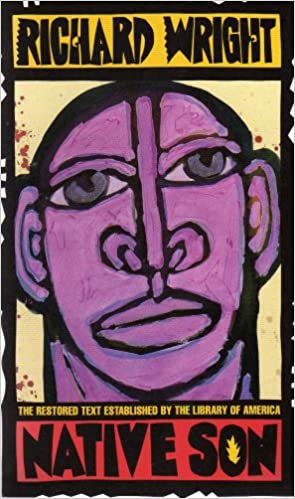

Book review: Native Son by Richard Wright

January 5, 2021

Native Son is quite possibly one of my favorite books I have ever read—it was entertaining and incredibly suspenseful while also maintaining a high level of historical accuracy that coincidentally directly links to current political tensions.

The novel follows an African-American boy named Bigger Thomas who lived in poverty during the 1930s. The opening scene gives an outright depiction of the poor quality of life Bigger was subject to: he wakes up in his one-bedroom home that he shares with his brother, sister, and mother, and they spend the first few minutes of their morning trying to kill a rat that is scurrying around the room. Just prior to this, Bigger and his brother had to turn around to avoid the shame of seeing their sister and mother get dressed for the day, since they did not have separate bedrooms to change in. In just the first few pages, Wright has already set a grim tone for the novel as readers continue to follow Bigger through his day in the third-person. But, also in the first few pages, readers are greeted with heaps of foreshadowing, but it is so subtle it hardly even seems symbolic. The rat is almost like Bigger, in a way—he repeatedly laments about his position in society that makes him feel like an intruder in a white man’s world, like the rat is an intruder in Bigger’s home. A window into future events also occurs when Bigger’s mother wonders why she even gave birth to him, a thought echoed in Bigger’s girlfriend later, when she also wonders how she fell into such trouble with him after she worked hard all of her life.

A sub-conflict that emerges in the first of three parts in the novel, titled “Fear”, is that Bigger must decide whether to take up a job offer from the Daltons, a wealthy white family that owns the neighborhood Bigger lives in. Bigger is held back from success by his group of friends, who have big plans to rob people, and are always getting into trouble. Wright presents an interesting red herring here; the troublesome crowd Bigger is involved in seems like it will be the central conflict of the novel, especially as Bigger gets into a physical fight with one of his friends. But, soon enough, his friends fade into the background when Bigger decides to take the job as the Dalton’s chauffeur.

The plot thickens when Bigger meets Mr. Dalton for the first time, and also his daughter Mary Dalton. Mary brings in elements of political tensions to the novel when she asks Bigger, out of nowhere, if he belongs to a union and calls her father “Mr. Capitalist.” Bigger, noticing Mr. Dalton becoming agitated about this, also becomes angry with Mary, fearing she will make him lose his job by asking him about political things, even though he does not even know what a union is. This is more foreshadowing—something Wright seems to be particularly fond of, but critics dislike as it plays into the lack of verisimilitude in the novel. Political ideologies, specifically Communism, become a scapegoat for Bigger later.

After this, Bigger is sent on his first drive as the new chauffeur. He is told to take Mary to her university, but instead, Mary convinces Bigger to take her to Jan, her friend (or boyfriend, it is largely unclear) who also shares Communist sympathies. Though racial tensions underlie Bigger’s and the Daltons’ relationship, the first explicit racial divide occurs when Bigger and Jan meet. Mary and Jan are self-proclaimed “friends to all” and support racial equality, but the way they go about it comes off in a very white-savior type of way. Bigger’s internal monologue is angry when he meets Jan, even though Jan is informal and goes out of his way to make sure Bigger knows he will treat him as a human being, because Jan has drawn the attention to their racial differences while trying to make up for them. Jan and Mary tell Bigger that they want to eat in a black neighborhood, wanting to see what it is like to live the way Bigger does. Bigger is even more angry and nervous, because first he had defied his boss’ orders, but now will also have to sit with white people at a diner in his neighborhood, where he earns lots of stares. A racial divide is also emphasized when Mary talks about how she has traveled to many places, but still does not know how people live in the black neighborhood; this shows Mary’s privilege and how she can belong anywhere, and that anywhere she goes is just a tour to her.

At this point in the book, it was still fairly unclear what the real conflict would be—Bigger’s struggle with poverty was perceived to be getting better as he had taken up a job with a generous and wealthy family, and his troublemaking friends were not recurring characters. That’s why the real conflict comes as such a surprise, and one of the reasons I love this book so much. You can’t see it coming.

When Bigger takes a drunk and stumbling Mary home, he is terrified of being caught carrying a passed out white girl to her bedroom; he had decided he couldn’t just leave her there on the front porch, where she’d wake up the family, and he would surely be caught after driving Mary somewhere against her father’s wishes. So terrified, in fact, that when he drops Mary in her bed and her blind mother walks in, Bigger covers Mary’s face with her pillow to prevent her from talking and giving away that he is in the room with them. When her mother leaves, disappointed in Mary because she reeks of whiskey, but believing that she is asleep, Bigger uncovers her face and discovers that he had accidentally smothered her to death.

It was an event I did not see coming in the slightest. It was ironic how Bigger was terrified of being seen taking Mary to her room because he believed his skin color would be reason enough for people to believe he was going to harm her even though he wouldn’t, just for him to actually harm her. But even at this point, the real conflict still hadn’t emerged, which is what I meant by this novel being incredibly suspenseful. The conflict was much deeper than a young boy trying to get away with murder, which is realized once Bigger gets caught by police towards the end of the novel.

The time in between is nothing insignificant though; one would think that Bigger would be remorseful after accidentally murdering somebody, but instead, he becomes completely unjustifiable. Only after getting rid of Mary’s body in one of the most gruesome ways possible, blaming Jan for the murder because he is a Communist, attempting to obtain ransom money from the Daltons, and then dragging his girlfriend into the crime only to murder her as well, was Bigger caught.

Jan’s friend, Max, decided to represent Bigger in court, not because he wanted to get Bigger off the hook, but because he believed that the conditions Bigger grew up in directly led to his crimes. Max wanted to save Bigger from the death penalty because of this. The court proceedings take up the better portion of the third part, and for good reason. For twenty-three entire pages, Max defends Bigger in a court of white faces that have been yelling racial slurs and insults in his face. But Max doesn’t defend Bigger’s crimes—he defends his humanity. He stresses that Bigger is only symptom of a problem and that sentencing him to death will do nothing for an entire community of people that can be pushed to a point of violence when they are treated as subhuman. He says that if a white man committed the same crime, the uproar would not be what it is for Bigger, and points to the debilitating socio-economic conditions that drove Bigger to his crimes. Throughout the novel, Bigger repeatedly said how he felt the most alive when he was committing crimes because he had been shoved into a box his entire life. Finally, he felt like how he thought white people feel in the world—free. Max delivers such an interesting speech, because it forces the reader to truly evaluate their morals. What Bigger did was absolutely unjustifiable, but it does not make him any less human. You have to take another look at your own privilege in society when you read this book; you may not be racist, but are you complicit to the racism surrounding you?

It is possibly the most disappointing, yet predictable, ending when Bigger is sentenced to death for his crimes. To me, this really hones on the moral of the story—you can force someone’s eyes open to the truth, but we will never be equal until they decide to open their eyes and take a look for themselves.